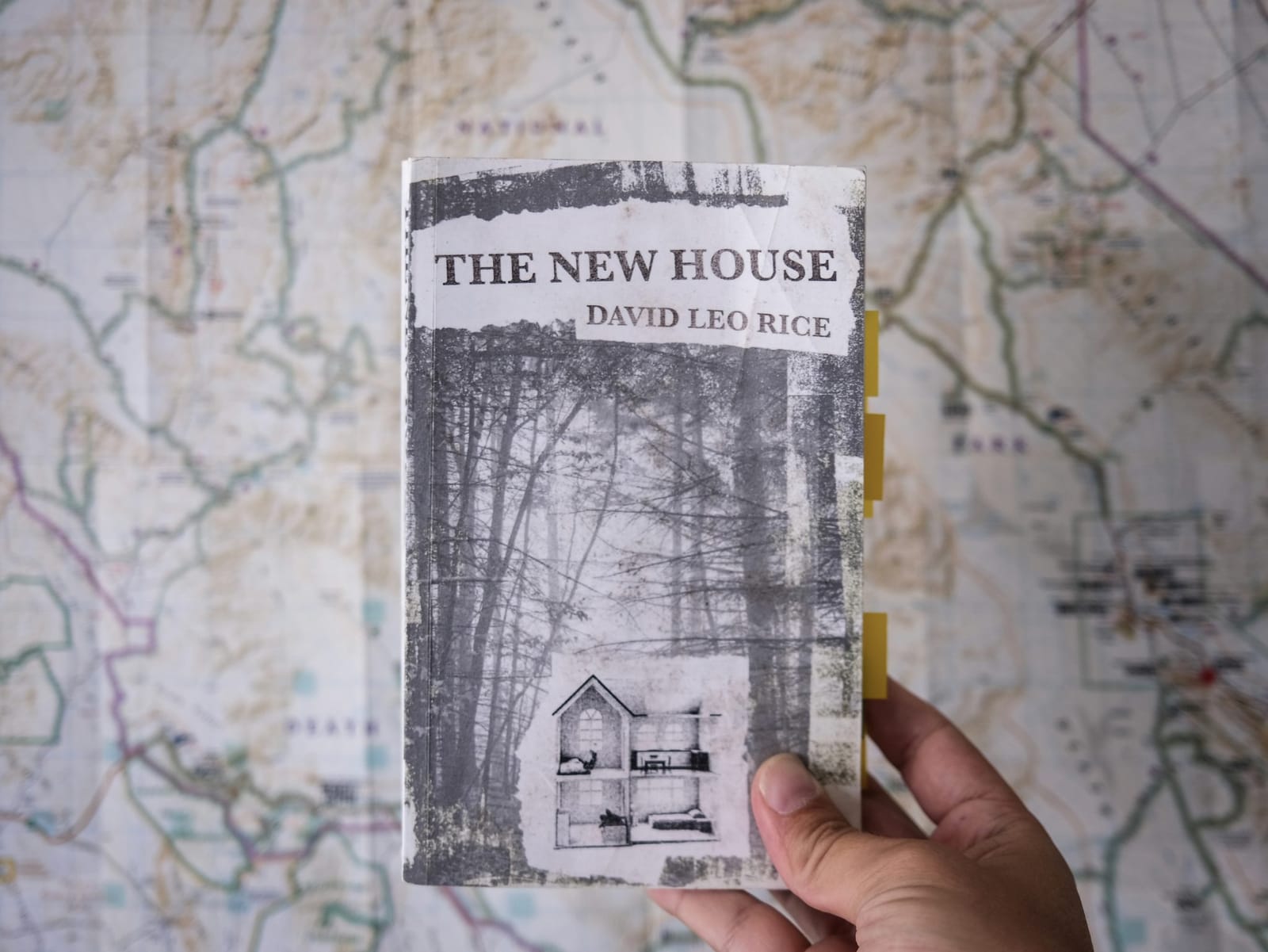

I can’t remember the last time I’ve dog-eared and highlighted so many pages in a novel. The New House by David Leo Rice has become an all-time favorite—an eerie, challenging, and delirious book that has burrowed into my thoughts like a seminal dream. It reads like the murk of limbic memory. And in parts, it reads like prophecy.

When a child wonders whether he is at the Trader Joe’s or a Trader Joe’s, it becomes “a question deep enough to knock on the locked doors of the sacred.” From here, the doors keep opening, one after the next, until they’re swinging like a mad cartoon, corkscrewing down into the muck of ambiguity, where things are one way yet possibly also the other way, and these endless forks generate a feedback loop of the paralyzing and the possible that feels like invention itself.

This is a fable about the headfuck of creation, and I want to press it into the hands of every artist, writer, and seeker I know.

Art-making intertwines with myth-making as we follow “an artist whose singularity will come close to justifying the entire American experiment.” He meets an enigmatic old woman who says, “When you show people images they’ve never seen before, something dead inside them comes back to life.” And this book teems with life as Rice conjures a world of shapeshifting bullies, talking drops of blood, and two villains known only as “the couple from another town”—all moving through a night “so deep it serves as a sort of anesthesia.” Likewise, Rice’s prose generates a hypnotic effect that lowers the defenses until moments of terror arrive with little more than a single phrase, like the mad butcher whose voice “is like that of a pig who’s been trained by some lonely pervert farmer to speak.”

Ancient mysticism collides with freaky Americana in a glorious mess through which Rice carves a precision-grade line between the liberating and the horrifying—two conditions that describe any creative endeavor, including faith. There’s a moment when the hero fumbles his way to a definition of art as “the brute dragging of heavy objects from the world in which they already exist into the world in which strangers, ignorant of their origins, can admire them in comfort.” Because when it comes down to it, as one character observes, most of us “want to touch the weird without fearing that the weird will touch them back.”

This book touches back.