1

“God is an experience,” an old man said as he reached for another cookie. “Not a thing or a concept. God is an event.”

Because hell can be described a thousand ways but heaven is impossible to grasp.

“God is an experience,” an old man said as he reached for another cookie. “Not a thing or a concept. God is an event.”

The bodhisattva was so overwhelmed by the suffering in the universe that the deity’s head split into eleven pieces. But then, seeing the deity's plight, the buddha gives Guanyin eleven heads to better hear the cries of those who suffer—and a thousand arms to help them.

Autechre’s “VLetrmx” is the correct song for contemplating the horror and beauty of living in the future.

Last night I woke up to tornado sirens. Wind rattled the walls and lightning filled our flat like a thousand camera flashes. We stood by the window and watched the howling dark, even though this isn’t what you should do in a tornado. On the local news, the weather people nervously discussed a map of angry red streaked with purple. Tornados in February were not normal, they said. But I’m learning to give up on normal. Global heat records have shattered for the ninth month in a row.

When the Atlantic washes over Interstate 95, will a new age of miracles be upon us? Will we conjure new gods to console us or continue to relitigate the beliefs from the past? American politics have taken the place of religion, always a scary sign, but there will be no miracles there. The candidates for president match the moment: exhausted and deranged. What comes after that?

As the world becomes more uncertain, are we easy marks for grifters, opinion merchants, and faith dealers? “Philosophy is no longer the pillar of fire going before a few intrepid seekers after truth,” wrote Bertrand Russell in 1946. “It is rather an ambulance following in the wake of the struggle for existence and picking up the weak and wounded.” Will the future deliver a new Vishnu or Buddha or Jesus Christ or Muhammad? Perhaps they’re already out there, asking you to subscribe to their newsletter.

I crave more mystery, more distance and shadow and myth. Today’s televisions come with a ‘motion smoothing’ effect that transforms movies into a nauseating hyperreal. I do not need 120 frames per second when the eye requires only 12 frames per second to imagine motion. It’s good to have a bit of chop and static, some fog on the stage.

The winter has turned warm again. Rain and fog and highs inching into the fifties. I write about the weather because it is the only thing that feels true these days. This country is becoming a hallucination, everyone committed to the reality they prefer.

Time to get serious about writing again. Two hours at the library every morning except Sundays. A dead simple schedule, something I can remember even though I’m not a morning person—but I can no longer wait for the day to get out of the way. There will always be demands and obligations, but they do not need me before eleven o’clock.

Last week, I fell hard for IBM Plex, an open-source type system that is dignified yet future-facing, which is nice because the current future does not feel dignified. I want the things I design to feel the same: crisp, cool, and sane. It’s a never-ending search for the line between clarity and personality, a quest that might apply to dealing with the self as well.

Last night, I sat in a half-lit conference room with eight very different men, and we discussed God, forgiveness, and making amends to those we’ve lost. One man scoffed at the idea. “Let the dead bury the dead.” Another spoke of time as a kind of god, that we live with all that came before and yet to be born, which meant our dead were with us now. And why not believe this? Why not believe my dead are waiting for me to speak to them?

But I do not. Instead I drove around Ohio listening to Sisters of Mercy.

The Joshua tree was named by Mormons in the 1850s, who thought they saw their prophet pointing to the promised land. I wonder what it would feel like to see prophets and omens in the landscape. “God is not interested in our theology but only in our silence,” writes Cormac McCarthy in The Passenger, which restates Psalm 46:10 from a human point of view: “Be still and know that I am God.”

Stillness has been in short supply these days, and I’m trying to puzzle out the relationship between peace and growth. Does growth require pain? Or at least some degree of tension? I have yet to hear someone say their life was bursting with love and tranquility and they couldn’t count all the money in the bank and that’s when they decided to get spiritualized.

The sun went down at 7:01pm, and the moon is full. When I stepped outside this morning, I saw my breath—the first frost of the season. Next month C. and I will drive into the desert to find a new place to live. In the meantime, I am savoring the heavier skies and reds and yellows. The burning leaves and earlier nights. Still working my way through The Bright Ages, Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry’s retelling of medieval European history.

There’s a story from the eleventh century about a French baron who would kidnap the locals and hold them in his castle for ransom. A soldier named Gebert rescued them, but they were soon recaptured and tortured. The baron punished Gebert by removing his eyes from their sockets.

“Gebert despaired of his fate . . . and decided to starve himself to death. But on the eighth day, he had a vision. A ten-year-old girl appeared to him, clothed in gold, suffused with light, and beautiful beyond description. She regarded him closely, then stuck her hands into his sockets and seemed to reimplant his eyes. Gebert awoke with a start to thank the girl, but no one was there. His vision began to return slowly.”

This was one of the many miracles ascribed to Saint Foy, a third-century girl who was burned alive after refusing to sacrifice an animal to Roman gods. Gabriele and Perry connect this story to a broader uptick in miraculous saints throughout the eleventh century, a time of destabilized power centers and decaying traditions that divided Western Europe “into fragmenting segments fraught with low-grade but constant strife.” For many, the solution was to invent new gods and new miracles.

Yesterday in twenty-first-century America, I idled behind a jeep with an InfoWars license plate. We’ve been creating fucked up religions lately to deal with uncertainty, casting each other as heretics and heathens. Hopefully, one day we will invent kinder gods and new miracles. Or at least better stories.

When she was a little girl, she would watch the darkness in her bedroom, hypnotized by the grey-pink flecks that seemed to dance in the air while she waited for sleep. One night, she climbed out of bed to tell her parents that she saw fairies in the corner of her ceiling. Her mother dismissed her, saying it was only a trick of the eyes, but a faint smile played across her father’s mouth as he tucked her back into bed. “We’ll talk later,” he whispered as he shut the door. They never did.

She eventually learned those shimmery dots were the natural interplay of retinal fluid and optical cones. But part of her still preferred to believe they were dancing pieces of darkness, the living material of the night. “Science shouldn’t explain everything,” she told me. She often succumbed to earaches and ennui, and she would watch the sparkles in the gloom, the rods and motes that flickered just beyond her vision. “Sometimes I thought God lived in the shadows of the ceiling,” she said, and she would gaze at the high corners of the room whenever she felt overwhelmed, half-expecting to find an answer there. “Some habits come strange and never leave.”

And some habits are infectious. Years later, I would find myself murmuring to the fluorescent lights at the Gas ’n Go or the drop ceilings of the church basements where people insisted on living a day at a time. Like her, I would search for answers in forgotten spaces with cobwebs and patchy paint jobs.

A gloomy Wednesday in Ohio with highs near 60. The sun went down at 8:30, there’s a waxing crescent moon, and I’m reading about God.

Here’s my first memory of God: I was five or six years old, crouched on the kitchen floor and feverishly rubbing a white crayon into a dark blue piece of construction paper. I still remember feeling a little crazy while doing this. I titled the resulting smudge “God” in the bottom right corner. The strongest part of this memory is feeling certain I’d uncovered what God looked like and not understanding why my parents weren’t more impressed with it.

This blurry scribble came to mind while reading Francesca Stavrakopoulou’s God: An Anatomy, which digs into the origins of the Judeo-Christian deity as a fleshy, breathing creature who was just as messy as the rest of us, prone to laughter, jealousy, and despair. He had parents (El and Athirat), and he moved through the world like we do, only on a grander scale. I like how Stavrakopoulou captures the psychology of three thousand years ago:

"The cosmic membrane separating the earthly from the otherworldly was highly porous and malleable, so that divinity in all its myriad forms could break through into the world of humans, whether it was perceived as a strange scent on the wind, a fleeting shape glimpsed from the corner of the eye, or felt at a powerful place in the landscape. But divinity was at its most tangible when materialized in images of the gods."

So I’ve been thinking about the cosmic membrane lately.

Cloudy skies, still no snow, and a high of 43 degrees.

There’s an old Roman maxim that fear gave birth to the gods. The historian Will Durant elaborates: “It was fear that made the gods—fear of hidden forces in the earth, rivers, oceans, trees, winds, and sky. Religion became the propitiatory worship of these forces through offerings, sacrifice, incantation, and prayer.”

How else could our ancestors explain thunder? But our fear of nature might be more frightening today because we know what’s causing all this drought, fire, flood, and plague—it is us. Meanwhile, the old gods have grown feeble. Our sites of worship were not equipped for today’s heat and speed. The church and the temple, the faith in free markets and human reason: it all feels a bit creaky. What new gods will today’s fears create?

Twentynine Palms. Sunset: 6:00pm. Sunny with a high of 80 degrees and lows in the forties. The Mojave desert is my favorite place on the planet. For fifteen years, this landscape has pulled at my thoughts like a magnet. Maybe it’s the cadence: Groom Lake. Chocolate Mountain Gunnery Range. Devil’s Hole. Mythic names that speak of salvation and redemption.

The desert is a land of religious vision, the home of desperate saints and ascetics dragging themselves across the sand in search of revelation. Airplane graveyards glint in the desert sun, perfectly preserved by the unoxidized air. I once heard about a woman who can tell your future by deciphering the contrails of experimental military aircraft. Driving out of the town of Mojave, there’s a sign that says, “If my people humble themselves and pray, I will heal their land.”

The desert offers a promise: drive a little further, keep racing through nothing and you might see something grand, something that will help you make sense of the world. A tragic ghost town. An abandoned gag shop that sold alien beef jerky during the UFO craze in the summer of ’71. A place in Death Valley where a woman performed an opera each night to empty seats. A historical marker where they detonated the first atomic bomb. And so much sky and land there’s nothing to think about except something resembling god.

A sunny Friday with a high in the 80s: a beautiful June day in the middle of October. I popped into the museum to visit my favorite Jesus: Antonello da Messina‘s Christ Crowned with Thorns, painted in 1470. Depicted at the moment Pontius Pilate presents him to the hostile crowd—behold the man!—he is “a Man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” (Isaiah 53:3). And it’s startling to see Christ looking so human, so plain. Messina has given him the face of a boxer, mashed and pleading, and those eyes are filled with bottomless sorrow—and maybe a sense of shock at what his very human pain will unleash across the centuries, what would be done in his name.

The flesh-and-blood realism of this painting emerged from an ancient belief in visualization as a form of prayer. Maybe it’s limbic and hardwired, this desire to see the divine rather than hear or touch. “And in grieving you should regard yourself as if you had our Lord suffering before your very eyes,” wrote Saint Francis of Assisi in the years before the Renaissance transformed painting into worlds that looked like our own. Inspired by the belief that visualization could lead us to God, these canvases became aids for contemplation. All the better if they left us damp with tears and blood. Seeking to clarify the role of the artist within the church, Cardinal Charles Borromeo’s Instructiones insisted that a painting’s only function was to move viewers towards penance.

I wonder where we find these images today.

My first concept of god came from It’s a Wonderful Life. I was four or maybe five years old, and I remember sitting on an orange-rust shag carpet with my parents’ knees behind me, all of us watching the pulsing globs of light that functioned as angels. Even today, it’s an unnerving sequence for me, far too existential for a Capra film. But I’m grateful that my first image of the supernatural was so abstract, rather than someone’s punishing god. Perhaps it’s fitting that it came from television.

This year’s holiday soundtrack is a collection of hymns and carols from the Welsh mines recorded in the village of Rhosllannerchrugog in 1959. These slightly haunted voices sound like my smudgy childhood memories of old black-and-white specials.

It’s snowing tonight.

When I consider the man I want to become someday, I often picture myself as someone who prays. I have no idea why this impulse is so persistent or where I would direct my prayers or why I haven’t yet become this man. But I enjoy imagining myself climbing out of bed and kneeling before a devotional image. Whenever I see someone unrolling a mat and kneeling towards the east, I envy the sense of orientation this must provide as their thoughts turn to otherworldly matters or the workings of the soul.

This morning I started reading Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, and I already know it will be an essential book for me. I’m only on page 40, but this feels like the most prescient American dystopia: a climate crisis that leads to desperate violence and reactionary politics. And Butler writes beautifully about god through the voice of a spiritualized fifteen-year-old:

A lot of people seem to believe in a big-daddy-God or a big-cop-God or a big-king-God. They believe in a kind of super-person. A few believe God is another word for nature. And nature turns out to mean just about anything they happen not to understand or feel in control of. Some say God is a spirit, a force, an ultimate reality. Ask seven people what all of that means and you’ll get seven different answers. So what is God? Just another name for whatever makes you feel special and protected?

But what is this urge to pray? My first thought speeds past the philosophical, evolutionary, and aesthetic reasons, and unexpectedly lands on a few lines from Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem:

It was impossible to expect a moral awakening from humankind itself, just like it was impossible to expect humans to lift off the earth by pulling up on their own hair. To achieve moral awakening required a force outside the human race.

It’s a challenging, even troubling thought, but it’s also humbling—which might be the point of prayer.

Last night I woke in the middle of the night and wondered if it’s possible to believe in something otherworldly in 2020. Maybe my attention span is too shredded, my brains too cluttered. How many people believe in some kind of god by necessity rather than choice? Are there people who don’t want to believe in God but are unable to stop?

I envy the ecstasies described by philosophers like Plotinus and Origen as they contemplated the realm of consciousness and eternity. Whenever I try to do the same, I only make myself anxious.

This morning in the park, I sat across from a woman who was talking to the pigeons gathered around her feet. She complimented their feathers as she tossed them bits of a hamburger bun. “Oh, you’re a beautiful one with little flecks of gold in your wings.” She giggled as they pecked and flapped, and it was a wonderfully roomy kind of laughter. “Don’t be afraid to express yourself,” she told them.

Something about the pitch of her voice, combined with her complete focus on the world she’d invented with these birds, reminded me of a song lyric that never seemed to end. This one thing I know, that he loves me so. I repeated the phrase for a minute until I remembered: “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” by Gavin Bryars, a 25-minute song attached to an anecdote with the qualities of myth.

In 1971, Bryars walked through a rough part of London with a tape recorder, taping drunken jive and street preachers. Then he captured the song of an unknown homeless man who would die within the year. Jesus’ blood never failed me yet. Never failed me yet. This one thing I know. Returning to the art department of the university where he worked, Bryars looped the man’s voice on a reel-to-reel player in a classroom. Then he went to get a coffee. “When I came back, I found the normally lively room unnaturally subdued,” he said. “People were moving about much more slowly than usual, and a few were sitting alone, quietly weeping. I was puzzled until I realized that the tape was still playing and that they had been overcome by the old man’s singing.”

Do I believe in god? I have no idea. But the persistence of this unknown man’s voice makes me think something like grace is possible. I hear it in the childlike wonder combined with elderly poise despite living in dire conditions. It’s built into the lyric itself, the blurred line between suffering and faith. And I think the pigeon lady lives in the same neighborhood: someone finding absolute pleasure and presence in a humble ritual while the world feels like it’s falling apart.

There are so many things I wish I’d asked my mother. Tonight I’d like to know about her favorite saints. I want to know what shook her faith for so many decades, and the energies that brought her back to the church before she unexpectedly died.

Today we crossed two million cases of coronavirus in the United States, yet the number hardly makes a dent. There’s a sense it’s all behind us now. Perhaps it’s the summer weather or the government’s negligence. Maybe we can only be vigilant for so long. If there’s a second wave of disease in the fall, I don’t think we’ll lockdown again unless people are exploding in the streets. This thing’s gone from novel to normal in less than three months.

Sometimes I wish I believed in something otherworldly, that I had an icon or figurine to kneel before. A lady who smoked extra-long menthols once told me that prayer is simply a form of directed thought. “That’s all it is,” she said. “So why not give it a shot?”

There’s an eleven o’clock curfew in New York City after last night’s violence by the police and the looting of some luxury stores by cretins. I flipped on the news and joined the nation in watching a moment of political theater so demented it boggles the soul. The President of the United States stood in the Rose Garden and declared himself the “president of law and order” while the police tear-gassed and flash-bombed a crowd of peaceful protestors to clear a path to a church across the street. Then our president stood before the damaged doors of St. John’s for ten seconds, waving a Bible in the air, possibly upside down.

A chorus of bishops, priests, and pastors condemned the president for using violence to get to church. Some of these religious leaders were among the tear-gassed. For too long Christendom has given spiritual cover to America’s ugliest impulses, and I pray this is the beginning of a Reformation.

A few hours later, UH-72 Lakota and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters descended on American citizens in a “show of force,” a military term-of-art for kicking up enough debris, noise, and dirt to frighten people away. To scare away the people asking the police to stop murdering black citizens. Cameras followed tense crowds while reporters discussed possible clashes and looting, as if willing violence into existence. A news anchor said, “We are descending into something that is not the United States of America tonight.” I’m not sure if this is true.

The amount of incense smoke that darkens a temple’s ceiling indicates the popularity of that particular god. I learned this last year in Taiwan, and it’s such a beautiful image: the accretion of so many wishes, prayers, and confessions painted in ash across the centuries.

Lately I’ve been wondering what the accretion of faith looks like in my own life, the mounting evidence of my little rituals and routines. Perhaps this journal is something like that, the nightly act of fumbling through the muck of the day’s thoughts, trying to articulate something sensible while the world grows ever more unsteady. But I’d like to find something more poetic and tangible, something closer to ash.

I remember watching the darkness in my bedroom when I was small, hypnotized by the grey-pink flecks that seemed to dance in the air while I waited for sleep. One night I climbed out of bed to tell my parents that I saw fairies in the corner of the ceiling. I still remember the disappointment when they told me it was just a trick of the eyes.

Eventually, I learned those shimmering dots are the natural interplay of light rays, retinal fluid, and optical cones. But part of me prefers to believe they are pieces of darkness, the living material of the night. Science shouldn’t explain everything.

Some habits come strange and die hard. I still watch the sparkles in the gloom, the rods and motes that flicker just beyond my vision. Although I no longer believe there’s magic among the edges of the ceiling, I still gaze at the high corners of the room whenever I feel overwhelmed, half-expecting to find an answer there. Maybe someday I’ll become an old man who searches for god in forgotten spaces with cobwebs and patchy paint jobs.

A chugging soundtrack for the midnight hour.

Whenever I get into a car, I want to point it toward the Mojave desert. I don’t think any photograph can capture the sensation of speeding down a desert road, the way all that blank land sends your thoughts cascading into rare spaces that blur the sacred with the profane. Maybe it’s the combination of so much spiritualized space dotted with motels that advertise color television and diners with fritzing neon that you can hear.

I once read the Ten Commandments taped to the side of a truck in front of an unauthorized Bon Jovi tribute concert near the Imperial dunes. “Everything’s a mystery and I’m just another small part of it,” said a woman at a gas station in Barstow. “Maybe that’s all I need to know.” Tonight her words echo in the same register as this maxim from Matisse: “The essential thing is to work in a state that approaches prayer.”

The desert feels like my future. When I imagine my life as an old man, I see myself searching the sky for saucers while listening to static at the outer margins of AM radio. A few years ago, I’d fall asleep thinking about Antarctica. Then came the Year of Lake Superior. These are the Nights of Slab City.

Strange how something you’ve heard a thousand times can suddenly knock you over. Maybe it’s a shift in the light, a stray fragment of head chatter, or a lack of sleep, but a familiar phrase can become vital and brand new. Tonight I sat by the window trying to rewrite my novel for the eighteenth time, but I was mostly staring into the middle distance and questioning my life choices while Leonard Cohen’s “Avalanche” played across the room. I’ve had this song in rotation for years because I admire how its spare guitar sounds like pure dread. Tonight this lyric in the fifth verse finally hit me:

I have begun to long for you, I who have no creed. I have begun to ask for you, I who have no need.

Those two simple lines capture what I’ve been trying to express in an 80,000-word manuscript. They describe my yearning to believe in something greater, some cosmic ethic or godhead. Is such a belief even possible in 2020? I’ve insulated myself with so many diversions that I wouldn’t know where to begin. What would it feel like to believe in the otherworldly? If someone truly believed in a hereafter or radiant glory, wouldn’t they go mad? Or at least struggle with answering emails or giving a damn about selecting the best dental plan?

But the logistics of belief aren’t nearly as interesting as the craving.

The internet says the lyrics are I who have no greed although one source says it’s creed, which makes more sense. I stopped pursuing the question after I glimpsed the insistent interpretations that say Cohen is singing about everyone from Christ to a serial killer. I worry my sense of the song would be destroyed if I tried unpacking it like an academic text—and to what end?

I’ve gotten in the habit of walking to the river each night to look at the sky. Lately I’ve been overwhelmed with the desire to know the language of constellations, the location of celestial bodies. It seems like a tragedy to go through life not knowing the names of the lights overhead.

There’s a touch of sadness whenever I watch the stars. I can’t help but search for my mom and dad up there. Although I do not believe in heaven, I remember the people I lost each time I stare into the night, obeying a nerve-wired impulse rooted in the magical thinking of the ancients. Two thousand years ago, the philosopher Posidonius introduced the most sublime image of the afterlife: “The virtuous rise to the stellar sphere and spend their time watching the stars go round.”

I’ve also found consolation in the words of Plotinus, who believed the stars have souls because “the heavenly bodies naturally inspire and make mankind less lonely in this physical universe.” Living in the final days of the Roman Empire, Plotinus turned away from “the spectacle of ruin and misery in the actual world to contemplate an eternal world of goodness and beauty.”

Difficult times can lead to otherworldly philosophy.

Tonight the few stars I saw in New York City looked cold, almost digital. Then I realized I was looking at an airplane.

They named the virus corona because it looks like a crown. Each night I join the rest of the city in dreaming garbled dreams about apexes and plateaus. Like so many others who are non-essential, my radius has been reduced to agoraphobic dimensions: living room to bedroom and back again, sometimes the corner bodega. Before sleep comes tonight, I want to remember space and motion. My thoughts immediately turn to the desert.

In the desert I drive fast and long because it’s a place of land-speed records and shattered sound barriers. Its utter stillness is a counterpoint for human motion. The Great Basin and the Mojave, the Sonoran and Chihuahuan. Desert logic deforms time and space. Soon it’s a quick hundred-mile drive to see a decayed military base or a wild sculpture made by conspiracy theorists and faith-dealers.

I never stopped in the desert, not even while crashed out in budget motels. Nerves still humming from the day’s driving, I’d stay hopped up on sound. The fritzing neon and grumbling ice machines, laugh tracks bleeding through the walls while long-haul trucks sped through the dark.

Tonight I want to find my way back to this sensation.

A desert-driving classic.

Now they’re saying the virus spreads by talking and breathing. We can kill each other just by being a person. One million infections worldwide, six thousand dead in America, and fifteen hundred dead in New York City.

And yes, I’m beginning to pray even though I don’t believe in much and I don’t know what to say. For now, I bow my head and hang on to a line from Voltaire: “Doubt is not an entirely agreeable state, but certainty is a ridiculous one.” An old man in New Orleans once told me that doubt is a conversation.

Some shops have signs taped to their doors: mask required to enter. We’re finally becoming a culture of masks in America. But the more critical shift is understanding that we wear them to protect others, not ourselves. And it’s a tragic twist, this spirit of collectivism borne from social distancing. Each day the American government reveals its staggering contempt for its citizens. We might finally take to the streets. But we can’t. Not yet.

Nights are getting weirder. So many sirens. Lone drunks vomiting in doorways. A man leans against a mailbox, eyes covered by a hood and hands pressed together like a prayer, mumble-chanting and grinning. Another ambulance speeds down First Avenue.

A late-night walk through the city to pick up some supplies and leave them outside my elderly neighbor’s door. I knock lightly and walk away like a prankster. So much can change in a week. I hear the undoing of a lock and her voice calling behind me. “Thank you, darling. Pray for me.”

The twenty-four-hour Walgreens on the corner is closed. Like a tragic bird, I smash into its sliding doors, expecting them to slide open. New York’s babble and hum have been muted. No more honking, laughter, or drifting music. You can hear your footsteps. And sirens.

Tonight I’m gripped by a wild urge to kneel in a church even though I have no religion or semblance of otherworldly faith. I think about the padded bar that flips down to cushion your knees, if it has a liturgical name or whether some denominations consider this a form of cheating. I think about the origins of the word knee, short and stabby.

I once heard a street preacher holler that we must drop to our knees and atone because kneel comes from the Latin for to know. Or that Leonardo da Vinci believed compressing the nerves in the knee generated spiritual thoughts. I don’t think any of this is true, this garbled information that came from god knows where. But these days kneeling before a neighbor’s door—or next to my bed while mumbling a makeshift prayer—is beginning to make some kind of sense.

I used to be so shy. There was a time when I would count how many words I said each day. At night I logged the number into a notebook. Sixteen. Twenty-three. Anything in the thirties was a good day.

This new season of self-isolation brings those quiet adolescent days to mind. The ambient chitchat among strangers has fallen silent because we’re told to stay home. No more talk about the weather at the café or mumbled apologies as we jostle through a crowded train. No more meetings, events, or dinners with unfamiliar faces where I would try to say clever things. All of that feels distant and silly now. Nobody needs my advice and I hold no fascinating opinions. Still, I don’t hope these quiet days don’t last too long.

We gather in the park because there’s no place else to go. Because we need to see the sky. We keep our distance and nod at one another, more aware of each other’s presence than before. Looking up, I see the first signs of spring and I remember reading something from Spinoza that said god lives in the trees.

The coronavirus continues to spread. Classes have been canceled and events are postponed. One thousand cases in America now and our government doesn’t seem to care. I wash my hands, keep my distance, and show up where I’m supposed to be. The subway seems a little emptier each time I ride it. Taking the train home tonight, I close my eyes and try my best not to imagine worst-case scenarios. I think about art and god.

The zips and color fields of abstract painting have never moved me beyond a chilly appreciation for their role in pushing art towards its vanishing point. Walking into Barnett Newman’s The Stations of the Cross, however, felt almost spiritual. The title does most of the lifting here, juxtaposing the mythic weight of violence and supernatural suffering against fifteen canvases of brittle monochrome. My eyes tried to map these stern lines and rectangles against the bloodshed and trembling on that day at Golgotha. But I could find no correlation, and I was left alone with that heavy title, those dispassionate shapes, and a woman sitting on a bench with her pencil paused in the air, hanging somewhere between contemplation and frustration. A security guard rocked on his heels at the edge of the room, occasionally emitting a rubber squeak that emphasized the hush of the gallery, a place with the secret air of an empty gymnasium after hours.

When the series was first displayed in 1966, Newman said these images were based not on the flagellation and martyrdom of the crucifixion but Jesus’s cry of lama sabachthani: Why hast thou forsaken me? “This is the passion,” he said. “Not the terrible walk up the Via Dolorosa, but the question that has no answer.”

And for a moment, I understood this sensation, a sense of utter vacancy, a hollowing of thought that left space for something greater. In my notebook, I scribbled this sentence: The denial of beauty leaves one greedy for any thread of hope, no matter how thin. This felt like a profound insight at the time, one of those camera-flash thoughts that comes bright and quick before fading forever. Artists like Newman and Mark Rothko insisted their blank fields of color were not academic exercises but spiritual statements. Although I feel lucky to have caught the briefest sense of this, I also left the room wondering if you can nail any damned thing to the wall as long as you attach it to the bloodshed and drama of myth.

Further reading: Barnett Newman; Valerie Hellstein, “Barnett Newman, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani,” Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014); the Stations of the Cross; Barnett Newman’s ‘Stations of the Cross’ draws pilgrims to the National Gallery

I remember standing before the gods on a rainy Monday morning in Taiwan. Once again, the question that haunts me when I approach any kind of altar: Am I allowed to pray before you if I don’t understand you?

And how do I pray? Forty-something years old and I still do not know how to pray even though sometimes I try. Thankfully these temples offered a clear ritual: toss two moon-shaped blocks, ask a question, draw a numbered stick, and receive your fortune from a machine. A beautiful collision of technology and ancient rites. Soon I was gripped by a Vegas-style fever as I tried to upgrade my “very inferior fortune” to a superior one. Setting luck and superstition aside, the simple act of articulating a wish was clarifying. It forced me to remember what matters most in my life, followed by a small catharsis. Leaving the temple, I passed an elderly woman in a t-shirt that said, “Stay wild and free.”

Woke from a dream that I was pounding on a counter demanding a cash-back rebate because my soul was damaged. This surreal sensation continued when I stepped outside. Ash Wednesday and people walked the streets with smudged crosses on their foreheads. A beautiful ritual, ancient and haunted. Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return. I envy the pageantry of Catholicism; it’s religion as art. Perhaps aesthetics can be a reason for otherworldy faith.

Today these smudges of ash looked a touch apocalyptic as coronavirus anxiety continues to take root. Squint a little and they might be a mark of infection or the protective omen of some new sect.

Flanked by health officials, the president held a rambling press conference and told us not to worry before blaming the Democrats. New infections are reported alongside articles that say it might not be a bad idea to gather supplies. Fill your prescriptions. Pick up some extra food and water. Be prepared for delays. How far will this thing go? Will history record this as a blip or is this the start of something bigger?

They’re caucusing in Nevada today. Voters organize themselves in the corners of gymnasiums and hotel conference rooms. The networks were not happy with the result. How can a socialist win 49% of a six-candidate field? Editorialists wring their hands. Meanwhile, an artificial intelligence program predicted the migration patterns after the seas begin to rise. The machine says tens of millions of people will flood into Las Vegas as well as Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, and Houston.

The subway seems more erratic lately. Short bursts of speed followed by sudden stops and lurches. We look up from our phones to see if anyone else is afraid. Maybe this is emblematic of something.

They did an MRI and said I have acute patellar tendinitis in my left knee. A physical therapist gave me a big green rubberband to wrap around my shins and taught me to do exercises with names like clamshell and butterfly. These are gestures no grown man should perform. I did not go back. I’ll live with the pain. I read an article about a woman who abandoned her children because she believed she’d been chosen to be raptured by god. I wonder if somebody like that experiences knee pain.

Everything’s on the fritz but it’s got a hell of a beat. See also: Sea level rise could reshape the United States, trigger migration inland.

The motel manager was unnervingly chipper when I checked in, a shine in his eye that could have been religion or drugs. Now he’s walking the perimeter of the parking lot at midnight, staring straight ahead and making perfect ninety-degree turns. I close the blinds. I think about praying, but I don’t know how. Instead I fall asleep thinking about the origin of the word hotel until I become convinced it is a portmanteau of home and tele. A distant home.

In the morning, billboards along Interstate 90 tell me that God owes us nothing, love is an action verb, and the key to forgiveness was hung on the cross. I drive with the windows down, thinking about forgiveness and my fifth-grade teacher. I wanted to play the saxophone, but she said my hands were too small. She made me play the violin, and I was terrible. At our Christmas recital, she told me just to pretend my bow was touching the strings. Her name was Mrs. Fiddler.

The towns in South Dakota have solid names like Reliance, Interior, and Alliance. A sign near a rest area says hundreds of victims of smallpox are buried nearby. Inside the travel plaza, giant flatscreens teach us the history of random celebrities. (Julianne Moore’s maiden name was Smith.) I wander the parking lot looking for my car, exchanging looks with a woman wearing a sweater that says, “I’m not bossy; I just get everything I want.” I stare at the electrified gates of golf courses named after slain tribes. I speed past a dozen military planes propped on concrete blocks like offerings to the machine gods.

Woke with a yelp from a tense dream of standing on a Russian coastline while pieces of my life washed onto the shore. Will I ever believe in god? If so, it will probably begin in my dreams. The first gods must have been born while we slept. How else could our ancestors explain the fantastic scenes that unfolded in their heads each night? God was little more than a ghost in the machinery of the subconscious before gradually being refined into a spirit, a concept, and finally, an animating force with ethical qualities. I often think about this phrase from Herbert Spencer: “God was, at first, only a permanently existing ghost.”

A haunted-looking priest stops in the middle of the sidewalk, staring at an advertisement for a career in nursing. “Maybe only 75% of my life was a disaster,” says a woman on the corner. “I don’t know, I never weighed it on a scale.”

An appropriate song from a perfect album that still haunts today. See also: Herbert Spencer.

I went to a 700-year-old church on Sunday morning and the service was purely tonal because I don’t understand Finnish. It was the most moving sermon I’ve ever heard. Bowing my head, I remembered a line from the poet Anne Carson: “I’ve come to understand that the best one can hope for as a human is to have a relationship with that emptiness where God would be if God were available, but God isn’t.” Perhaps this is enough. That, and the grandeur of a pipe organ reverberating across a vaulted stone ceiling while candles flicker in the gloom.

Now begins the season of Arvo Pärt and private hymns for a better year. On New Year’s Day, I sat in the pews of a medieval cathedral in Turku, Finland. Completed in 1300, its tower featured the first public clock in Finland and it standardized the time for the entire region. Since 1944, the cathedral’s chiming bells have been broadcast on the radio each day at noon. There is something deeply reassuring about this ritual, knowing that a sound with a traceable source of stone and bronze has unified listeners for so many years.

I studied the painting of the Transfiguration over the apse, a scene that depicts the moment Jesus became radiant after traveling to a mountaintop to pray with Peter, Paul, and John. The prophets Moses and Elijah appeared in the clouds and a voice from the sky called him son. Why would Jesus not think he’d gone insane?

My mind drifts into a time beyond church bells and paintings and desert prophets. Standing in line at the supermarket the other day, I was suddenly overwhelmed by the idea that the world existed long before there were eyes to see it. This nervy sensation followed me into this cathedral. The realization that evolution might provide us with unimaginable senses tens of thousands of years into the future. That I will never know how this story ends or why it was written.

Only a few days into the new decade and we’re already overwhelmed by headlines about missiles, fires, drones, government paralysis, and dangerous weather. America is circling the drain. Australia is burning. A craving for new spiritual paths shaped the 1960s before boomeranging into the materialistic 1980s. Is this need resurfacing in our age of digital alienation and climate crises? I worry the future will become a breeding ground for religious extremism, cults promising to restore our screen-addled brains, and faith-dealers peddling solace in a scary new world of flood and fire. In the meantime, I bow my head and try my best to pray to god knows what.

Further reading: Turun tuomiokirkko; Transfiguration of Jesus, painted in 1836 by Fredrik Westin.

Big Wheeling Creek Road runs through the hills of West Virginia and dips straight into the uncanny valley where a pair of thirty-foot gurus dance against the naked winter trees. Maybe it’s their bug-eyed grins, flowy arms, or brightly painted skin—something about these statues bothers the soul. They’re too lifelike. Too chipper. And they’ve deeply complicated my ideas about West Virginia.

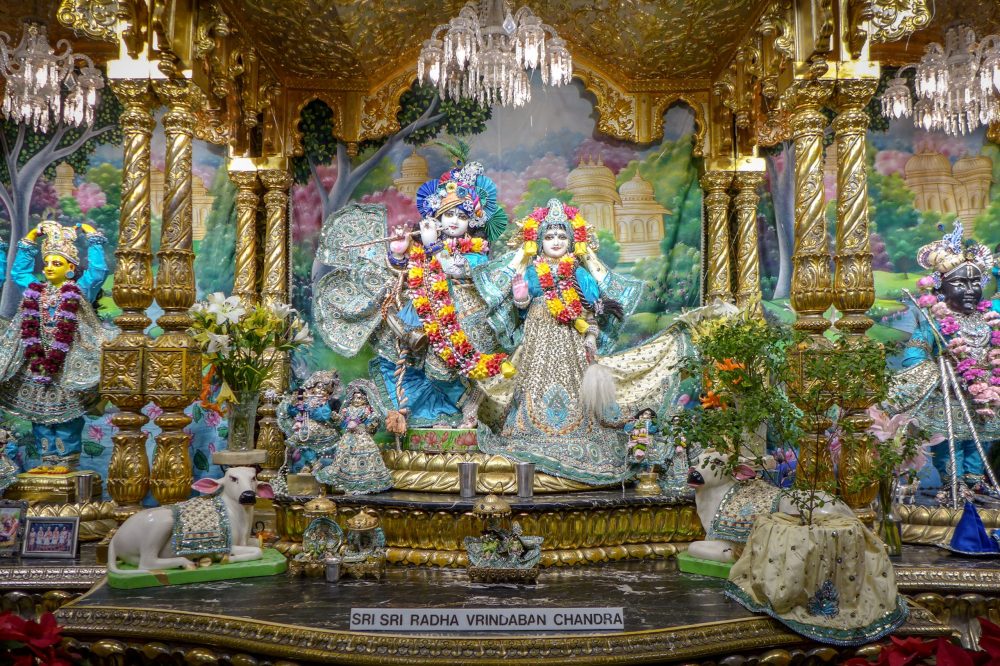

There’s a massive gilded palace that looks like a postcard from a distant time and land. A life-sized plastic elephant sleeps in the parking lot. Gazebos surround a man-made pond where a sign warns about the possibility of violent swan attacks. Surveillance signs say Krishna is Watching. This is the campus of New Vrindaban, once the site of America’s largest Hare Krishna community.

Since its founding in 1966 in New York City, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness has become comic shorthand for the wild-eyed ideologue you endure in subway stations, airports, and crowded streets. Or rather, the ones who find you. The street preacher and proselytizer, the faith-dealers armed with trinkets, literature, and impossible questions. Do you know the truth? Have you been saved? Where will you spend eternity? But I cannot fault their enthusiasm. Given my excitement whenever I discover a new favorite book or song, I can only imagine my behavior if I thought I’d found some kind of god. If I ever peek behind the veil and see the secrets of the universe, I’ll probably want to tell people about it too.

The woman at the welcome center caught me off guard. I expected a hard sell for conversion. Instead, I felt as if I was signing in to see my dentist. “Feel free to wander around the grounds,” she said, offering a map. “When we built this place in the 1970s, we built it with love. If we needed a chandelier, we’d go to the library and read about how to build one, and we’d make the best chandelier you’d ever seen. It was beautiful because we worked for free. Because we worked with devotion. Not like today.” She gave a sweep of her hand as if gathering the broken pieces of a vision, a tiny gesture that somehow summed up the indignities of end-game capitalism.

The temple was a vast polished floor beneath an ornate ceiling of carved teakwood. Black metal cages lined the walls, holding imprisoned gods and idols. A lion-headed Vishnu. Bug-eyed creatures, spangled saints, garlanded gurus, and yes, very beautiful chandeliers. All of this was monitored by a disturbingly lifelike recreation of the Hare Krishna founder, Swami Prabhupada. A gold watch glinted on his mannequin wrist.

Young faces with bright teeth fill New Vrindaban’s brochures, faces straight from central casting for one of those docudramas we know by heart by now: the idealistic American utopia that veers into something darker than the world it hoped to replace. A quick search of “New Vrindaban” is appended by words like scandal, abuse, and murder. A 1987 headline from the Chicago Tribune: “Murder, Abuse Charges Batter Serenity At Big Krishna Camp.” A year later in the Los Angeles Times: “Hare Krishna Swami in Prison for Killing Serves as Guru to Inmates.” Ten years later in The New York Times, 1998: “Hare Krishna Movement Details Past Abuse at Its Boarding Schools.” In the wake of two dead bodies and rumors of sexual abuse and drug trafficking, New Vrindaban’s guru faced charges of racketeering, mail fraud, and conspiracy to murder two ex-members who said he was abusing children. After hiring Alan Dershowitz as his defense attorney (see Mike Tyson and OJ Simpson), Kirtanananda Swami served two years of house arrest. A few weeks after his release, he was caught molesting a boy in the back of a Winnebago.

Yet another tale of people hungry for meaning falling prey to a charismatic predator who stripped his flock of their possessions and dignity. Moments of violence are happening right now in every corner of the world, but when these stories emerge from utopian communities, they feel far more damning: proof of a nagging suspicion that there’s no such thing as harmony in any society. That no matter how far-flung we travel or how spiritualized we become, the wickedness of men will find us. A line from Voltaire’s Candide comes to mind: “If hawks have always had the same character, why should you imagine that men have changed theirs?”

When it opened in 1979, Prabhupada’s Palace of Gold was heralded as America’s Taj Mahal. “A spiritual Disneyland,” the newspapers called it. As New Vrindaban’s membership and finances dwindled in the wake of the scandal, the palace fell into disrepair. The painted teakwood began to flake. The 22-carat gold leaf started to peel. But today the temple is back in fighting shape, part of an ongoing renovation funded in part by the community’s decision to lease its land for natural gas drilling. Returning to the car, I remembered the cynical little gesture of the woman at the welcome desk. Then the palace shrank in the rear-view mirror, vanishing behind a curve like something I had dreamed.

As I drove out of the hills toward the interstate, the Christian mega-churches, American flags, and billboards for faster download speeds, adult videos, and all-you-can-eat buffets seemed as spectral as America’s Taj Mahal, a collective hallucination like any other. I thought about our dogged faith in the fiction of nations and money and fame. All of it growing rickety, ready to be replaced by something new.

The choral drift of Popol Vuh’s ‘Aquirre I Lacrima di Rei’ sounds like glaciers, mist, and devotion. After listening to this song six times in a row, it occurred to me that the word ‘theology’ means the ‘logic of god’—which seemed profound at 35,000 feet.